The Taboo of Being Afghan: The Absence of Afghans’ Cultural Representation in Iranian Museums

Sajedeh (Sarah) Bijanikia

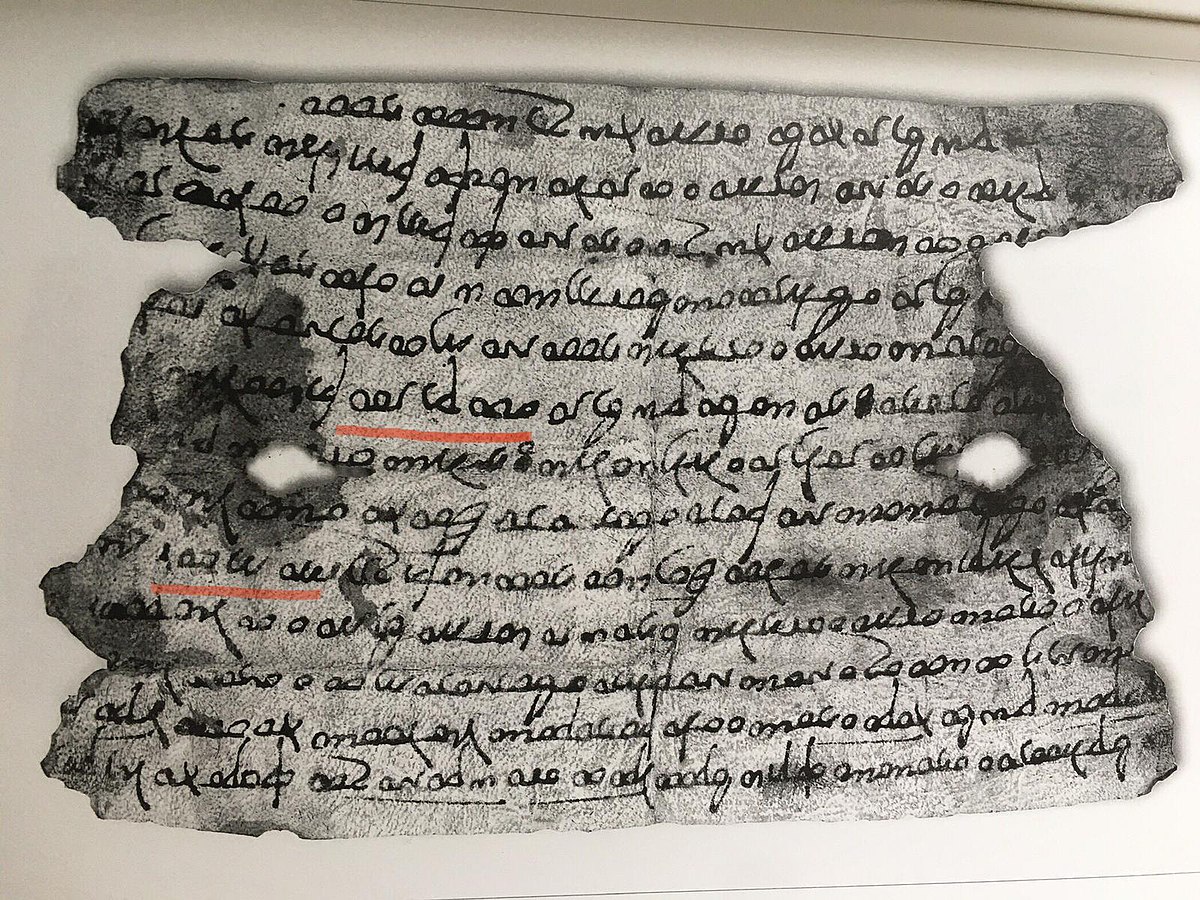

Bactrian document in the Greek script from the 4th century mentioning the word Afghan (αβγανανο): "From Ormuzd Bunukan to Bredag Watanan, the chief of the Afghans"

Abstract

Afghan culture and Identity suffer from miss-representation in the Iranian context. From the Safavid era to the present time, this miss-representation has manifested itself in various forms, in a way that Afghan nationality is even considered as a curse in the present-day Iranians’ arguments. In addition, political and cultural institutions have reproduced this inequality. In such situation, Iranian museums can pose as a resistance base in themselves, cultural hubs for Afghans to remind and represent their heritage. What policies and strategies, then, can Iranian museums formulate to realize such objective? With a combination of descriptive-analytical and critical methods, this study analyzes the obstacles and possibilities towards this problem.

Keywords: Museum representation, Afghan culture, immigrants, Iran

Not just out of Desperation

Long before the internal conflicts in Afghanistan, the Afghans have considered Iran as an accessible choice for migration and finding occupations. This region, for instance, has long been considered as a stepping stone for Hazarah young men who desired to acquire independence and the financial requirements for starting a family. The period of conflict started in 1978, with a coup that installed Nur Mohammad Taraki’s government, following which the Soviet Union’s intervention took place in an attempt to handle the power struggle between the two factions of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan. This marked the beginning of Afghans’ flee to the neighboring .countries including Iran and Pakistan

Civil war, insurgency against the communist rule, Mujahideen’s resistance, the Afghan war, the U.S -led bombing campaign, and later the rise of Taliban dislocated and led millions of Afghans towards the Iranian and Pakistani borders. Yet, in addition to those seeking asylum in the foreign lands, there is a considerable population of Afghan immigrants who had already “settled and integrated into Iranian society in the 19th and early 20th century” (Adelkhah & Olszewska, 2007, p. 140). This can suggest that in some cases, as Monsutti believes, migration has been a choice and ‘a way of life’ for these people (Monsutti, 2004, p. 186, as cited in Adelkhah & Olszewska, 2007, p. 140).

The mobility in the Afghan lifestyle and their constant transition between several localities of their own country during warm and cold seasons reveals a vital fact about their local culture which must be taken into account when studying the Afghan immigrants and refugees in other geographic and cultural contexts. Countless male Afghans choose labor migration due to the seasonal agricultural cycles, so that they can work in the coal mines of Pakistani Balouchistan after their harvest and before the next farming season. This conveys the reality of immigration in Afghan eyes: an opportunity for better living conditions, even at the largest costs. As a result, when it comes to real hostile situations such as war, drought, economic and political crises, migration poses as a fine option for the people of Afghanistan.

Still, one must accept the difficulties of such courageous decision. Being housed temporarily or permanently in refugee camps, exposure to a slightly new culture, building a new life from scratch in a foreign land, enduring xenophobic manners, complying with new norms, identity crisis, and temporary residence permits are a few examples.

Afghani as a Curse word

Every Iranian has sure heard an adjective exchanged in some disputes at least once in their life: Afghani. This aching truth alarms us about an injustice daily inflicted upon Afghan migrants in Iran. While they mark the largest population of refugees residing in Iran, they are still not accepted culturally. Based on the 2020 report by UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), 800,000 refugees currently reside in Iran, 780,000 of which are indicated to be Afghan. In addition, 2.6 million undocumented Afghans inhabit either in Iranian urban areas including Tehran, Mashhad, Isfahan, Fars, Kerman and Qom or rural areas. But why being Afghan signifies as an insult exchanged between Iranians when they try to belittle each other? And why Afghans are considered as contemptible ‘other’ in the eyes of Iranians?

This issue needs to be regarded in light of the history of Iranian nationalism. First started in the rule of the Qajar dynasty (1796–1925) and with the exposure of Iranian monarchs and aristocrats to the European military and technological advancements- especially during two wars against Russia (1804–1813 and 1826–1828) - Iranians felt the need for modernization and aspired to amend their cultural and technological lag. Several Qajar intellectuals aspired to discuss this issue paleontologicaly, some blaming the emergence of Islam and some calling out the rulers’ despotism and the lack of constitutional law. No matter how fruitful these studies have been, they hold a close connection to nationalistic ideas gradually rising in that era. As Zia argues,

“Iranian nationalism is intimately and organically intertwined with the intellectuals’ fear of, and infatuation with, things and ideas European, and their anxiety to bring Iran to the same level of advancement as soon as possible (Zia, 2016, p. 18).”

Ironically enough, in opposition to this European ‘other’, much emphasis has been put on Iran and Iranians. In an attempt to redeem or even deny these underdevelopments, countless replications of various European innovations were fabricated, a great example of which is the Homayouni Museum in 1874. Later, in the Pahlavi dynasty, this modernization came along with Iranian Archaism sanctioned by Pahlavi to legitimize themselves by affiliating their rule to the Achaemenid Empire (550-330 BC).

This reverence towards the Europe can be interpreted into Iranians’ contempt towards themselves. Concieving their picture in the European eyes as left behind, lagged, and even un-progressed, and trying to retrieve the glory of ancient Iran, Iranians seem to have been stuck between self-loath and self-admiration. This position can finely explain the discriminations occurred to Afghans residing in Iran. Just as they imagine to be loathed by Europeans, Iranians mirror themselves in Afghans, and inflict the same intolerance towards them.

While Iranian identity posits itself as a totem, a feature that connects all Iranians under one flag, Afghans- as foreigners- are believed by most Iranians to have been violating this sanctity by their mere residence in Iran. In addition, while Afghanistan was once a part of the Iranian terrain, the sanctioned history narrated especially by school books perpetuate this otherness. A great example is the claim of Afghan invasion as what marked the fall of the Safavid dynasty in 1722 by Shah Mahmood Hutak, known by Iranians as Muahmud the Afghan. The problem with this narration is two-fold: first the fact that there are several historians who believe that Mahmud’s motivation for the siege of Isfahan was the Safavid king’s incompetence, and not just a whim for conquest; and second, the contemptuous tone of this name called by Iranians is quite telling of how they perceive Afghans: a taboo.

Representing Afghans

The cultural apparatus in which Iranian mind has been wired is trained to see Afghans as those who once invaded Iran, and not those who were once their compatriots. Yet, in light of this intolerance and lack of cultural acceptance in Iran, the necessity for retrieving Afghans’ rights as human rights and representing Afghans fairly manifest themselves. In response, no political apparatus has been authored. Efforts for introducing NGOs have been insufficient and sometimes miss-representing Afghans (Adelkhah & Olszewska, 2007), and no Government in exile has been formed in Iran. These shortcomings- not only in fairly narrating the history, but also in providing a resistance base- later affects Afghans’ representation in museums.

A minimum of four common characteristics can be named for Iranians and Afghans, whereas none is impartially represented in Iranian museums. Not only they have a lot in common historically, they both speak Persian language and share the same literary history. In terms of religious beliefs, both countries have Shia and Sunni Muslims as their largest religious population. Even concerning ethnic diversity, they share such ethnic groups as Baluch and Turkmen.

Nevertheless, none of these features contributed to a sense of sympathy and brotherhood, and neither the official education system nor the public policy have been able to address this prejudice. In terms of jurisdiction, there is a grave silence towards Afghans’ problems in Iran. Although several generations of Afghan immigrants have been living in Iran for decades, no Afghan can own real estate in this country. While an Iranian man can marry an Afghan woman and be sure of the law to consider his child as Iranian, it is not the same for an Iranian woman marrying an Afghan man and bearing his child. Speaking of the labor law, Afghan laborers are never considered the same as Iranian laborers, and Afghans are prohibited from most occupations. By what means, then, can Afghans resist these biases?

No place can represent the problems of being an Afghan in Iran better than museums. Aside from the silence and probable reluctance of these institutions to identify and represent Afghans, their objects and collections still possess considerable fragments of Afghan identity which must not be overlooked. Furthermore, the way some museums like the National Museum of Iran, as the Iranian reference for other similar institutions, chooses to represent the Afghan subject through their artistic and material culture manifestations, can compensate to this injustice from the bottom up.

Based on the inclusion framework suggested by Sandell, Nightingale and Dodd, the museums’ area of practice can be divided into three intertwined branches each of which guarantees and completes the other: representation, participation and access (Dodd and Sandell 2001, Sandell 2007, Nightingale, and Sandell 2012). When it comes to the Afghan community, the museums’ measurements need to devise for all these three aspects. In terms of access, when an Afghan visitor enters a museum, most curators and museums visitors identify them based on their appearance and accent, which usually biases their impression. This can explain why there are quite few museum visitors with Afghan inheritance in museums of Iran.

When it comes to participation and representation, representatives of the Afghan community need to be consulted with and interviewed in order for the museum to realize features and objects by which Afghans identify themselves. In that way, both curators and the Afghan community can be ensured of the fairness of the exhibitory outcomes. Nevertheless, several structural deprivations exclude Afghans from museums, which are only hoped to be lifted gradually and by the help of such cultural hubs.

Bibliography

Adelkhah, F., & Zuzanna Olszewska. (2007). The Iranian Afghans. Iranian Studies, 40(2), 137–165.

Monsutti, A. (2004). Guerres et Migrations: Reseaux Sociaux et Strategies Economiques des Hajaras d'Afghanistan, Neuchatel:Paris.

Sandell, R. (2007) Museums, Prejudice and the Reframing of Difference, Routledge: London and New York.

Sandell, R., & Nightingale, E. (2012). Museums, equality, and social justice. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Sandell, R., Dodd, J. (2001) Including Museums: Perspectives on Museums, Galleries and Social Inclusion, Department of Museum Studies, University of Leicester.

Zia, R. (2016). The emergence of Iranian nationalism: Race and the politics of dislocation. Columbia University Press.

UNHCR. (2021, Dec 31). Overview of Iran operation. Operational Data Portal. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/country/irn

Download the PDF file: The Taboo of Being Afghan-Absence of Afghan representation in Iranian museums Sajedeh Sarah Bijaniki